Left to the imagination, winemaking is simply the hand-picking of grapes from sun-kissed vines and patient aging in oak barrels. However, modern production often includes the use of additives to enhance flavour, stabilize the wine or mask defects. This may cause digestive upset, food sensitivity flares or even mood swings.

Here is a brief rundown on common additives, their regulation, benefits, potential drawbacks and how you can make informed choices about the wine you drink.

Fining Agents (e.g., Egg Whites, Casein, Gelatin)

Fining agents help to clarify and stabilize wine by removing unwanted particles. Their use is widely accepted but the use of egg or milk related products must be disclosed on the label since these items may result in an allergic reaction by anyone sensitive to them.

Glyphosate

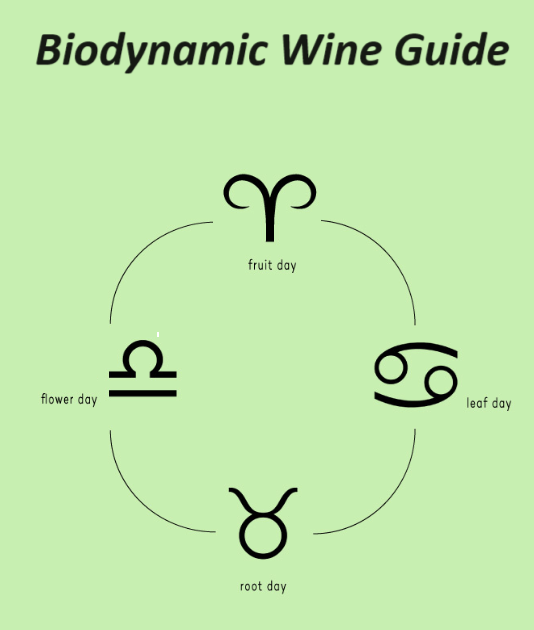

Glyphosate is a widely used herbicide. Traces of glyphosate may be found in wines due to vineyard herbicide use, generating concerns about long-term health impacts. Its use is closely monitored though trace amounts have been detected in some wines worldwide. While levels are generally below health risk thresholds, the presence of glyphosates enhances the value of organic and biodynamic wines.

Mega Purple and Colouring Agents

The use of Mega Purple and other colouring agents is permitted in moderation in accordance with wine production laws and is not required to be disclosed on the wine label. Overuse of these materials can conceal flaws and mix flavour profiles.

Sugar (Chaptalization)

Sugar is used to increase the amount of alcohol generated during the fermentation process for cool-climate wines as natural sugar levels may be insufficient. Some wine regions permit their use while others do not. For example, it is prohibited in the southern wine regions in France but accepted in their northern wine regions. Overuse of sugar can make wines taste unnaturally sweet.

Sulfites (SO₂)

Sulfates are included to preserve freshness, prevent oxidation, and reduce microbial growth. Their use and quantities permitted are regulated though the limits vary by country. Most people can safely consume sulfites but anyone sensitive to them, particularly those with asthma, may suffer headaches or redness in the face. However, this is rare and these reactions are often confused with other sensitivities.

Tannin

Tannin is needed to make wine age-worthy. The grapes are full of seeds which are very tannic. The seeds are crushed with the grapes to add structure to wine. Small amounts of oak chips or tannin powder may be added to the wine as well.

Tartaric Acid

Tartaric acid is used to balance the wine’s acidity to improve the taste. Regulators considered its use safe and it is widely used in small quantities. If too much is used, the wine can taste sharp and be unbalanced.

Yeast and Nutrients

These are used to initiate fermentation and the different kinds of yeast affect the flavour of the resulting wine. The use of yeast is widely accepted among the wine producing nations. Overuse can result in mixed flavour profiles.

Minimizing Additives

To minimize the inclusion of additives in the wines that you drink, look for organic, biodynamic and natural wines as these minimize or eliminate synthetic additives and chemicals. Low-intervention wines are wines that have fewer additives. They will be labeled as “natural,” “minimal sulfites,” or “no added sulfites”.

Explore local wineries as smaller producers often have more transparency in their winemaking processes and may use fewer additives.

Natural wines are made with grapes and time, delivering pure flavours showcasing their origins. They prove that great wine doesn’t need artificial help. Avoid mass-produced wines for example, Apothic, La Crema, Ménage à Trois and Yellow Tail. Instead, investigate lower production wines that are often found in the specialized section of the wine store. In Ontario, that would be the “Vintages” section of the liquor store.

Wine additives are not fundamentally unsafe, but understanding their role can help you make choices aligned with your health and values.

Sláinte mhaith